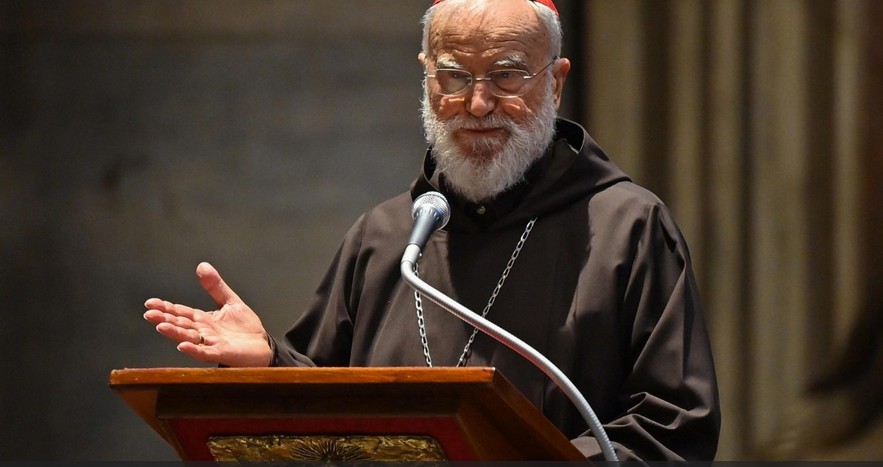

By Benedict Mayaki, SJ

Aside from the many evils caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been, at least, one positive effect from the viewpoint of faith: that of making us “aware of our need for the Eucharist and the emptiness that its lack creates.” In his first Lenten Sermon for this year, Cardinal Raniero Cantalamessa, the Preacher of the Pontifical Household, invites Christians to “rediscover the Eucharistic wonder” because every little progress in the understanding of the Eucharist “translates into progress in the spiritual life of the person and of the ecclesial community.”

He notes that speaking on the Eucharist in this time of the pandemic, and now amid the horror of the war, does not mean turning our eyes away from the dramatic reality we are experiencing, but rather helps us look at it from “a higher and less contingent point of view” as the Eucharist “offers us the true key to the interpretation of history.”

Eucharist in history of salvation

The Eucharist, the Cardinal says, “is coextensive with the history of salvation” and is present in the Old Testament as a figure, in the New Testament as an event, and in our time – the time of the Church – as a Sacrament.

In the Old Testament, examples of the Eucharist as a “figure” include the manna, the sacrifice of Melchizedek, and the sacrifice of Isaac. With the coming of Christ, and the mystery of His death and resurrection, the Eucharist became an “event,” something that occurred in history – a unique event that took place once and is unrepeatable. Then, in the time of the Church, the Eucharist is present in the sign of bread and wine, instituted by Christ.

To renew and to celebrate

In practice, the difference between the event and the sacrament, he points out, is in the difference between history and the liturgy. To trace the link between the sacrifice of the cross and the Mass, St. Augustine distinguishes between two verbs: “to renew” and “to celebrate.” In this light, the Mass renews the event of the cross by celebrating it (not reiterating it) and celebrates it by renewing it (not just recalling it).

Therefore, in history, there was only one Eucharist, the one carried out by Jesus with His life and death. On the other hand, according to history, thanks to the sacrament, there are “as many Eucharists as have been celebrated and will be celebrated until the end of the world.” Through the sacrament of the Eucharist, we mysteriously become contemporaries of the event as it “is present to us and we at the event.”

Liturgy of the word, Eucharistic prayer

Focusing on the Eucharist as a sacrament, Cardinal Cantalamessa explores the development of the Mass in three parts: Liturgy of the Word, the Eucharistic liturgy (the Canon or Anaphora), and Communion, adding at the end, a reflection on Eucharistic worship outside the Mass.

He notes that in the earliest days of the Church, the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist were not celebrated in the same place and at the same time as disciples participated in the worship services in the Temple where they read from the Bible, recited psalms and prayers, then went home afterward to gather for the breaking of bread. This practice was given up following hostility from the Jewish community and the disciples no longer went to the Temple to read and listen to Scripture but instead introduced it into their own places of Christian worship, making it the Liturgy of the Word that leads into the Eucharistic Prayer.

Reading the Scripture in the Liturgy “helps us to know better the One who makes Himself present in the breaking of bread, and each time it brings to light an aspect of the mystery we are about to receive.” This is what stands out in the experience of the disciples of Emmaus when they recognized Jesus in the breaking of the bread.

Not only hearers

The words of the Bible being spoken, and its stories retold at Mass, are relived in a way that what is remembered becomes real and present “at this time,” “today”; and we are not only hearers of the Word but we are called to put ourselves in the place of the people in the story.

When proclaimed during the liturgy, Scripture acts in a way above and beyond explanation and mirrors how Sacraments act. The divinely-inspired texts have a healing power that has led to some epoch-making events in the course of the history of the Church, as a direct result of listening to the readings during Mass. For example, the Franciscan Movement began in Assisi when a newly-converted young man and his friend went to church and the Gospel of the day was Jesus saying to His disciples “Take nothing for the journey, neither walking stick, nor sack, nor food, nor money, and let no one take a second tunic” (Lk 9:3).

Homily preparation

Cardinal Cantalamessa highlights the Liturgy of the Word as the “best resource we have to make the Mass a new and engaging celebration each time we celebrate it.” In this regard, more time and prayer need to be invested in the preparation of the homily.

He notes that relying on one’s knowledge and personal preferences to prepare a homily and then praying to God to give add His Spirit to the message is a good method but “isn’t prophetic.” Conversely, to be prophetic, the first step is to ask “God for the word He wants to say,” then consultation of books, the Fathers of the Church, teachers, and poets. In this way, it is no longer “the Word of God at the service of [your] learning, but [your] learning at the service of the Word of God.”

The work of the Spirit

The attention to the Word of God alone is not enough, the “power from on high” must descend on it, the Cardinal says. As the action of the Holy Spirit is not limited only to the moment of consecration alone during the Eucharist, so also the Spirit’s presence is indispensable for the Liturgy of the Word and communion.

Scripture “must be read and interpreted with the help of the same Spirit through which it was written" (Dei Verbum, 12). In the Liturgy of the Word, the action of the Holy Spirit is “exercised through the spiritual anointing present in the speaker and listener.” Anointing is given by the presence of the Spirit; and thanks to baptism and confirmation – and for some, priestly and episcopal ordination – we already have the anointing imprinted on our soul in an indelible character (2 Cor 1, 21-22).

The anointing “does not depend on us to create it, but it depends on us to remove the obstacle that prevents its radiation.” Like the woman in the Gospel (Mk 14:3) who broke the alabaster jar and the perfume filled the house, we are to break the alabaster vase: the vase is “our humanity, our self, sometimes our arid intellectualism” through faith, prayer, and humble imploration.

In this light, we should ask for the anointing before setting out on preaching or an important action in the service of the Kingdom. This anointing is not only necessary for preachers to effectively proclaim the Word of God, but also for listeners to welcome it.

Not that human training is useless; it is, however, not enough, the Cardinal says. “It is the interior teacher who truly instructs, it is Christ and His inspiration who instruct. When His inspiration and His anointing are lacking, external words only make a useless noise.”

VaticanNews

Italiano

Italiano Français

Français