The idea for these mobile schools came from Brother Camille Véger. In 1979, he read a letter sent by Father André Barthélémy, who was the National Chaplain for Gypsies at the time, to the Superior of the Lasallian Fathers in France, calling for volunteers to "educate young gypsies of the Parisian suburbs who are poorly prepared for the rapid changes of today's world”. This letter inspired Brother Camille to engage with the nomads, to help "young gypsies who remain distant from other young people who despise or ignore them, but who are also tempted by everything that urban society has to offer”. Brother Camille responded to the call, volunteering to face a new pedagogical challenge, and responding to his concern to give priority to marginalized young people, often excluded from access to knowledge. "If these children cannot go to school”, he said, “then the school must go to them”. Now all he had to do was put the idea into practice.

Preparation

Brother Camille prepared for a whole year: he learnt the Roma language and attended courses in basket weaving, ceramics and painting. He felt these activities would be useful when working with young nomads. During the same year, he travelled around France to find out more about pedagogical experiments already being carried out in schools set up in municipal reception areas. He soon realized how in tune the teachers were with both parents and children: mostly because, instead of the children going to school, it was the school going to the children. They were being taught in their homes, under the careful supervision of their families.

Purchases

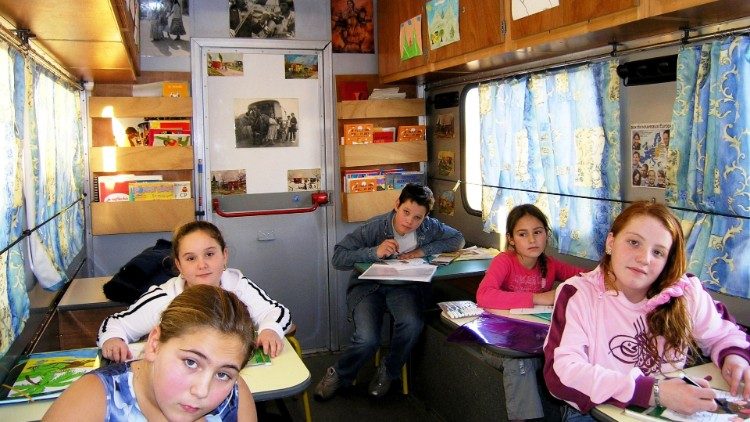

Purchasing a vehicle is the first step towards opening a mobile classroom: freedom of movement is essential in order to take the school from one group to another, to the city outskirts, or industrial areas, to a garbage dump or a cemetery, or a field. The Parisian Province of the Lasallian Fathers was excited about this project to provide education to the marginalized, and decided to pay for the first van. The problem was finding a vehicle large enough to accommodate six to eight children for each session during the school year. "The first vehicle", explains Brother Camille, "was a small second-hand van that was roughly equipped, and belonged to a couple of pensioners who used it as a camper. To get things done quickly, I simply removed its contents and added some folding tables, which we fixed to the walls, with the help of an experienced craftsman. He helped us prepare several other vans, opening side windows next to the door”.

Test runs

Brother Camille began by teaching reading to young gypsies every Wednesday afternoon. Using a 10-card game approach, he taught them very quickly how to recognize the consonants and the 10 basic sounds of the French language. A number of children of all ages came in for reading lessons within the first few weeks. While they might have been afraid of a traditional school, they couldn’t wait to board this van where they learned to read quickly and well. Perhaps because the mobile school was more familiar with their environment. Their families, meanwhile, considered the school van a gift from heaven: their children were learning to read and to recognize road signs, names of medicines, and much else that would be useful to them life.

September 1982

The experiment was a success. A formal request to open a mobile classroom was accepted, and authorization was granted for a three-year trial period. The first "official" mobile classroom took to the road in September 1982. The School Van’s first stop was a nomad camp composed of around 150 caravans. The Pentecostal Pastor with authority over the community introduced himself, and the mobile school received a warm welcome. Brother Camille remembers that moment: "The children were jumping with joy and shouting: 'School, school! We’ll learn how to read’”. “We also created a kind of reading certificate", continues Brother Camille. All the children who passed their first reading test received the certificate, and kept it carefully in their pockets. It is important to note that this level of basic education is all that many young gypsies will get throughout their lives. "This result may have meant little to us. But to them it meant a lot", says Brother Camille.

Trained teachers

Education inspectors come regularly to evaluate teachers working in the mobile vans. Usually they are impressed and often give unexpectedly high marks, says Brother Camille. "At the end of my class, an inspector called me out of the van after ninety minutes of uninterrupted classes to tell me how grateful she was for introducing her to a kind of school she didn't know. She said she was amazed at the young Roma’s hunger for knowledge”. At the end of his career, when he retired in 2003, Brother Camille scored 19 out of 20, which attracted the interest of the Ministry of Education for this new type of education for a hitherto largely ignored population.

New funding

With success like this, the Christian Brothers had to organize themselves to come up with new funding each year. The Lasallian communities had largely participated in the first eight years of the project. Now that academic authorities recognized the reputation of the initiative, local communities were approached and contributed financially. The Christian Brothers received various grants as well. The number of mobile classrooms steadily increased over ten years, until there were 35 school vans operating in major cities like Paris, Lille, Bordeaux, Perpignan, Lyon, Grenoble, Toulouse and Tours. Most of the mobile classrooms are administratively connected to Lasallian network schools. The others work in collaboration with the Federation of Associations for the Education of Children and Young Gypsies in Need. In France, mobile classrooms educate about three thousand nomad children.

From vans to buildings

In recent years, the number of school vans has slightly decreased, but that is not necessarily bad news. Closer connections have been created between established schools and mobile branches. In Toulouse, in particular, children share a kindergarten between the mobile classroom and the traditional school. A school bus, driven by a teacher, transports older children to a local high school. The school no longer goes to the children. Today it is the other way around. Exactly what the Christian Brothers worked towards for so long.

Jean Charles Putzolu - VaticanNews

Italiano

Italiano Français

Français